Years ago, living in Colorado, my first husband shared a studio with an older artist who painted alpine scenes. He was a man of few words who spent long stretches of time hiking and climbing in the Rocky Mountains. He worked on each of his paintings for equally long stretches of time. He painted very classically, using a muted palette and often used oil paints. A lot of his work had a brooding quality, as did he.

I was young and full of energy, ambition and hubris, and it never seemed like his side of the studio had much going on in it. I mostly steered clear. But one day I dropped by and was struck dumb by the small acrylic piece he had left propped up on his easel. It depicted a sliver of a mountain skyline and was rendered so perfectly, I felt I was up on a trail above the treeline myself. I stared at its spare, perfectly placed brush strokes in awe, seeing that he’d intentionally left the top corner unfinished so that the blue sky faded out into blank paper. Looking at it, I could feel the thin air, the awesomeness of the mountains, the sense of the unreachable beyond. The painting was likely more of a study for something larger, but I loved it as it was, something about the unfinished bit making the painting that much more special.

I remembered that painting this week as I’ve been thinking of how the unfinished bits, the missing and absent, the blank spaces and silences can say so much. So often I’m still striving for the answers and a sense of completion but the gaps sometimes point the way better than anything else.

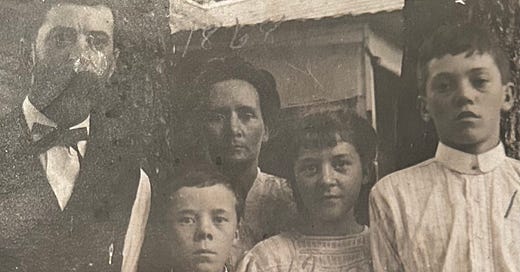

This came up the other day after spending a chunk of a day revisiting my family’s genealogical record, ‘The Crooks Book.’ My great Aunt Charlotte began compiling the book the year I was born, when she was 70 years old and spent more than a decade collecting and assembling census records, military documents, family trees, old photos and more. This was before the Internet, DNA tests and things like Ancestry.com! Amid the compendium there are also snippets of her writing: “Farm Life” and “A trip to Grandmother's” and “Train Travel.” There's a hand-written bit by her brother, my Great Uncle Henry, about assembling a 'prairie schooner’ for a move across town. Fascinating stuff about times long past that tend to make me nostalgic and proud and slightly amazed that I’m even here..

My sister had the book for a while, and she began to update some of its back pages with information about our generation’s lives. She left when I was still married to my first husband and my brother was in the Marine Reserve and my nieces and nephews were babies. About a decade ago, the ‘Crooks Book’ landed with me and the implication that I’d keep it updated. At the time, I scanned The Crooks Book into PDF form so that all of my siblings had copies, but I've been stalling on what more to do with the actual book since.

Opening the book is like visiting family, equal parts nurturing and reactivating. Especially because so many people in the book are no longer alive. On Memorial Day, I was thinking about my dad and Aunt Charlotte. And while they survived, most of their lives were defined by the three years they each spent serving in World War II. Those two were my people in my family, the ones I miss the most on days when I’m wanting some familial comfort, and the older I get I see their time in war being a large part of why that was. They had been through literal war, they had no obvious delusions left, and I trusted them to see things, and me, clearly.

This latest review of the Crooks Book both reinforced some of my assumptions and chipped away at others. As I paged through the thick, yellowing book, I marveled anew at how much of my current, increasingly vulnerable comfort, owes to the efforts of a line of family members who left their home countries to serve in a succession of early American wars while surviving battle and travel, diseases and accidents. Civil Wars, World Wars. Generation after generation signed on to fight and serve without any apparent hesitation. But as I reviewed the book’s contents this time, I also saw how all that bravery was complicated by so much that was unspoken, and unacknowledged, about whose country this was.

Charlotte’s narrative begins to pick up in the early 1800s, unsurprisingly, as the US expanded westward. That the right to that expansion came at the expense of the rights of Native Americans was so normalized within the family culture, at least in this record, it's barely remarked upon. From the 1800s on out, the Crooks Books is a record of farm life alternating with war stories, wagon trains and steamboats, trains, and ‘horseless carriages’. Children are lost in childbirth; 18-year-old soldiers die of measles; a great, great uncle returns from the Civil War on the same horse he left on years earlier… and the shadows of Native Americans loom throughout.

No railroads and only the poorest wagon roads, mostly Indian and buffalo trails, led through Kentucky, on through Indiana, into Illinois. The first record of George Washington Crooks is found in Western Illinois. He could have made the journey by wagon train or he could have taken the river route ....”

George marries in Illinois and makes his way to Christian County in 1837.

“This portion of the country was known in that early day as the “Black-Hawk hunting ground,’ and was widely known as a fine hunting region. Game of all kinds was abundant. At the close of the Black Hawk War, 1833, there still remained as residents of the county, a fragment of the Indians who were mostly Kickapoo….”

In 1866, after the Civil War, George sold his Illinois property and moved his growing family to the Ozark Highlands of Missouri. There, Aunt Charlotte is born at the end of the 1800s, and enjoys a somewhat idyllic childhood for her first 12 years.

“Missouri has mighty springs that start full grown, boiling out from underneath a high wooded bluff. Clarkson Big Spring is one, and this Big Spring had been a favorite camping ground of the Indians under Chief Sarcoxie. I remember picking up many Indian arrow heads on the farm after each plowing (1906).”

I have long loved Charlotte’s longer meditations on life on the farm, how their lives revolved around the seasons, how bucolic it all seemed. Today I looked up the origin of the word Missouri. It means "people with canoes (made from logs)" or "one who has dugout canoes.”1 Now I wish I could ask Charlotte if her family knew any of those tribe members, what they thought of them and their place .

“People were busy with their lives,” a friend who studies history shrugged when I brought up my increasingly complicated feelings about my family’s whole-hearted participation in Westward Expansion. How when something is so normalized it becomes invisible. How so much of this sort of scenarios is playing out in different places around the country. And how one always has to start from where they are now… while time marches on.

As it did for Charlotte. Amid the relative bounty and comfort of the farm and advances in train and car travel, disease, not war caused the first series of shifts in Charlotte’s life. Her mom, my great grandmother became ill with tuberculosis at a time when “fresh air and raw eggs were believed to be a cure.” Pivots and moves were made accordingly. There’s a move to Colorado for its sanitariums; another trip to California after her mother dies; and a return to Missouri. Charlotte evenutally goes back to Colorado where she is married and enjoys day trips on mountain roads before her relatively young husband gets pneumonia and dies. After that, nursing school and when war breaks out, nursing soldiers overseas. Across the country, her nephew graduates from Mission High School so he can enlist, too.

Decades later, I knew my dad and Aunt Charlotte to have a quiet pride in their service done with conviction and a sense of what was right, knowying they had done what needed to be done.

“Now is the time to be brave,” one of the many, many emails about signing something or donating money to a campaign, read. In this case, someone had just decided to run for office, which I had to agree was courageous. I didn’t give the candidate any money (not that they weren’t worthy!), but I have been mulling what being brave means in this current reality.

Meanwhile, the Crooks Book is sitting on my desk while I consider updating the entries about my generation, what I want to include, what I might leave out, inadvertently or purposefully, and what I might amend.

“Missouri History What is the Origin of "Missouri"?” https://www.sos.mo.gov/archives/history/history